Poetry for people who don’t like poetry

Non-fiction, poetry, tutorial

So much ‘poetry’ is utter crap, worthily boring, cheap doggerel or pretentiously incomprehensible that it’s no wonder many, if not most, people are put off.

This book shows where the good stuff is, why it’s good stuff and why it’s special. It’s not for school children as it takes maturity to appreciate reflections in the puddle of life’s experiences.

As well as the backbone of descriptive skill and being the voice of a writer with something to say who knows how to say it concisely there are the two completely forgotten elements.

1 The heart of a poem is at the end.

In most cases, where there is a ‘show…discuss’ sort of structure there will be a concluding section. It probably doesn’t reiterate what’s previous, but it will hand the reader a pole and pegs and say to the reader “I’ve made the tent, now you put it up.”

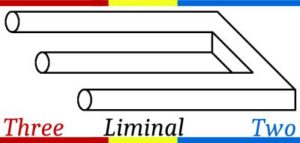

2 Liminality

Poetry is meant to mess with your mind. It is meant to be bonkers. It is fairy tales for grown-ups. The start of Cherry-Ripe by Thomas Campion goes

There is a garden in her face

Where roses and white lilies blow;

A heavenly paradise is that place,

Wherein all pleasant fruits do flow:

There cherries grow which none may buy

Till ‘Cherry-ripe’ themselves do cry.

Woaah! That’s impossible. Well of course it is. That’s what slows us down to read something into the words not just read the words.

In W.B.Yeat’s The Dolls the inanimate dolls discuss the arrival of a real baby in the doll-makers house. Once you think about it, wouldn’t it be strange if they didn’t discuss this imperfect intrusion. (In the book there’s the full poem and discussion, but here you’re on your own. It’s also a good example of the heart at the end of a poem.)

Let me draw you a picture

Carl Sandberg |

|

Fog is a cute little poem worth putting in your pocket. It’s also a brilliant example of liminality. Fog doesn’t have any sort of feet! Neither does it have eyes to ‘look’. Utterly bonkers! The picture on the right, sometimes called a blivet, is also impossible. Put your finger over any section and it’s incomplete but ‘possible’. Now replace ‘Three’ with ‘Fog’ and ‘Two’ with ‘Cat’ and you begin to see how they are connected.

What is it describing? Fog you say? What about a cat? Mixing ideas together is one of the great clevernesses of good poetry. For example it’s easy to forget about fog and see a cat jump onto a wall, sit looking at we don’t know what for quarter of an hour, then jump down about its invisible business. That’s two things that take no notice of you as they come and go.

The layering of ideas in a poem doesn’t have to be descriptions of faces and gardens, fog and cats. It can be emotions, what-if, conflict, challenging assumptions or a loose-end of the reader’s mind being caught in the mechanism.

Not available

If you know any publisher prepared to challenge modern posey then this needs to be turned into a properly produced book where the originals, my notes and biographical details can be combined into something to cherish.

| Jump in | ||

| Fog | Carl Sandberg | Cute, non-rhyming. Bonkers in a nice mixed-up way, which we’ll explore |

| Any news of the iceberg | Les Barker | Funny without being doggerel. Bonkers. Tricks your emotions. Best Titanic poem ever (there were lots). |

| You and I | Roger McGough | Contradiction at word and character level. You can’t hit a target when it’s a hole, so what does a poet do instead? |

| Where we differ | W H Davies | Similar but different to above. Conflict and frustration need a second look. |

| Blow, blow, thou winter wind | W Shakespeare | He did have his good points! How structure can be used for different moods. A ton of metaphors. |

| Paint me a picture | ||

| The sunlit house | Charlotte Mew | Sharp description followed by feellings which won’t quite stay still |

| Signs of Winter | John Clare | Superb description in 14 lines. Odd words fit perfectly. Poetry can be a window on history. |

| White sunshine | Lesbia Harford | The oddity we accept of anthropomorphism. Reversal of metaphors. |

| Drugs made Pauline vague | Stevie Smith | Snapshot of people’s lives. Speculation can be fun. Twist in the ending. |

| Armies in the fire | Robert Louis Stevenson | See how the scene changes from outside to inside to in the mind. The technique of a great poet drawing you in. |

| From a railway carriage | Robert Louis Stevenson | Rollicking rhythm. Fun and excitement. Is this a back-to-front poem? The fantasy is at the start and the description follows. No! He’s describing the magic of train travel. |

| Night Mail | W H Auden | To compare with the above. Look up the film. Each section has it’s character. All history now. (Atypical Auden!) |

| Cherry-ripe | Thomas Campion | What nice things to say. A whole wheelbarrow load of similies from 400 years ago. Subtle tension in the poet’s mind. |

| White Heliotrope | Arthur Symons | Evocative memories of a liaison. Suggestive symbols yet no overt emotion. |

| Dance of the hanged men | Arthur Rimbaud | A horrible description. How stanzas keep the pace and reader going to the end one bite at a tiume. |

| Tell me a story | ||

| Sea Lullaby | Elinor Wylie | A vivid description of the sea’s moods but everything you see is in your head. Rhyme, rhythm and verse form are ideally suited to ‘…and then …and then’. Each verse is like a sentence with ‘something going on’. Pathetic fallacy |

| The Quiet House | Charlotte Mew | Too long or an illustration of entanglement through soft compliance? (Warning: Lots of ‘I’ poems are dire. Pam Ayres has never written anything else God help her!) |

| The Bird of Paradise | W H Davies | A superb study of people and their tattered edges. He brings the reader right into the scene. |

| The Tay Bridge Disaster | William McGonegall | An excellent job (as intended) of straightforward reporting. No sublety but it does have a propr heart at the end. Discussion of the Emperor’s New Clothes when it comes to fire-hose ‘posey’ poets. |

| My Busconductor | Roger McGough | …So why is this word-soup not crap? It uses evocative words oddly (liminally perhaps) which slows us down to register something of the mood. It has a proper ending.

|

| Ballad of the Harp-Weaver | Edna St.Vincent Millay | Tales to be read out aloud so as to share the melodrama. A truck-load of the supernatural which builds-up to the inevitable. |

| Emotion and relationships | ||

| Witch-Wife | Edna St.Vincent Millay | The beginning starts with negatives…

Millay doesn’t know how to grasp this love herself so is it any wonder she leaves us uncertain as well. Obviously a voice can’t really be like coloured beads… Except what happens if you pull a string of beads through your hand? There’s a sort of chattering. |

| To my Valentine | Ogden Nash | Wow! What an overflowing fusillade of negatives. We like bonkers novelty and contradiction.

|

| Little Green Buttons | Shel Silverstein | A cartoon from a real cartoonist. It’s fun but also has deeper roots we can sympathise with. |

| The Dolls | W B Yeats | A sad situation told by dolls! Liminal! The dollmaker has nothing to say and his wife just an an apology at the end. There’s a subtle balance of conflict and shared trauma. |

| Wife Killer | Vernon Scannell | More liminal fantasy presented as reality (until the end) with brutal words packed into small punches. |

| In the Night | Stevie Smith | Contrast to the previous poem. She wants to bite people: What sort of person is that? |

| Until this cigarete is ended | Edna St.Vincent Millay | A farewell to love poem. I don’t believe she’s really done when this cigarette is ended. The power of emotions can be painted subtlely. |

| Spellbound | Emily Brontë | Stormy moors is Emily’s home ground. This is confusing. She’s painting her turmoil and doesn’t or can’t explain. |

| Tickle me | ||

| The Tiger | Hillaire Belloc | It’s really good fun (and educational) to share short silly things with children. |

| Anteater | Shel Silverstein | One cartoon in four lines. Silly. Fun. |

| Reflections on Ice-breaking | Ogden Nash | A quip to remember. |

| System | ||

| Life | ||

| To Virgins, to Make Much of Time | Robert Herrick | Could be a quip or perhaps worth remembering the whole of the first verse. Or even all four verses. When good poets say things well then perhaps we should quote them. |

| The men that don’t fit in | Robert Service | A ‘frontiersman’ ballad with accentuated rhythm. There is a place for such plonk-de-plonk verse and this is it. I know people just as he describes. |

| In the country | W H Davies | This is about poverty. Davies makes it interesting enough to reach the end and then realise there’s something strange going on. The only reference to the countryside is in passing in the first line. Eh? Oh! Now I see! He means ‘country’ as in ‘Nation’. He’s clearly frustrated… But what can you do? That’s ‘you’ as in ‘you the reader’. It’s our problem not just mine is the moral. |

| This be the verse | Philip Larkin | Oh my giddy aunt! Rude words. I know an illeterate man who has this as his (only) favourite poem. |

| So We’ll Go No More a-Roving | Lord Byron | This is a very simple poem, which I’ve included as an example of how it’s possible for anyone to write something that makes sense, fits together and carries a message. |

| Old Men | Ogden Nash | I like this because it encapsulates a way of life for old men hugging their pints in the pub. Simple but perfectly observed. |

| The road to Kerity | Charlotte Mew | Creepy and horrible. Youth looking at the ghosts of age looking at the waves that might take them away. Treachery in memory. |

| The Wayfarer | Stephen Crane | Read this aloud and see how he makes you pause. It’s short and simple… But there’s a moral in a one-act play of eleven lines. |

| Reflection | ||

| Résumé | Dorothy Parker | Ways to kill youself dressed-up as funny. Does she come across as desperately miserable? No, I don’t think so. She’s being sardonically witty with a minute postscript of ‘pity me’ in the corner. |

| Candle | Edna St.Vincent Millay | There’s a febrile attitude going on here. I may be overdoing it but I don’t care. A writer’s version of eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die. |

| The Small Hours | Dorothy Parker |

Empty sleepless nights summed-up. Note her little song tells us she was happy once. Here she’s exhausted by emptiness rather than determined to do something about it. |

| The Men Who Wear My Clothes | Vernon Scannell | Yet more sleepless nights. The images he paints are ghosts of himself.What they have in common is And all of them looked tired and rather old so he also is feeling tired and rather old. |

| Wild Lightning | Suzanne Doyle | An example of a poem that fails at the end and isn’t very sharp throughout. What to do about stuff we don’t like? |

| Fifty Faggots | Edward Thomas | Is this peace? More premonition of his death in the trenches. (One reason for looking at the biographies of poets is how they interacted with contempories. Robert Frost spent time together with Thomas, wandering the English countryside and pondering what to do about the war. Frost’s The Road Not Taken was written to Thomas about the issue of whether to enlist.) |

| The Owls | Charles Baudelaire | First sit us down, then tell us something. When we’re spooked then add an ending to emphasise the fulity of fighting fate. |

| Mood and philosophy | ||

| Jerusalem | William Blake | Clever hook at the beginning suggesting by questions that Jesus was pottering around the home counties. Then he nails his colours to the mast. No wonder it became a song. |

| Little boy lost/Found | William Blake | Of course this is a moral tale. Trust God and he’ll see you home safe. Just like fog with feet, so God has a hand to lead the boy. Of course it’s bonkers… but it makes sense in the context of the scene. |

| Crossing the Bar | Alfred Lord Tennyson | Notice the smooth flow of the words which are easy to say. Superb craftsmanship. (Poetry at funerals has become traditional, but just as you don’t send Auntie Flo off in a box knocked up from a door, a shelf and that wonky kitchen cabinet, so perhaps research what the professionals have done first.) |

| Waiting for the Barbarians | Constantine Cavafy | The picture of a classical town is shown to be nothing more than a warm-up for the ‘here-now-us’ message at the end. That’s how poetry should work: Mixing tales and our lives. |

| Who has seen the wind | Christina Rossetti | This is more than a poet reflecting, it makes us reflect for ourselves. To me it’s a heads-up to readers that when the trees are bending we should stop and ask what’s passing by. Time as well as the wind. |

| Uphill | Christina Rossetti | Unambigious metaphor. |

| Goodfriday, 1613. Riding Westward | John Donne | Not a normal first-choice of his work. (Have a look.) Included because it is historically significant and mostly incomprehensible for a modern reader… But the analysis has been done for you on-line. Poetry that lasts tells us something about humans not just fashions of the times. |

| Mess with my mind | ||

| The River | Sara Teasdale |

The whole poem is black and white no-nonsense description… Yet we’ve also got pure emotion pouring out as well. She’s sharing riveryness and bitterness. She did have some miserable relationships. |

| The Solitary Huntsman | Ogden Nash | That’s unusual! A nursery rhyme with a mysterious huntsman, a huntsman that might take threescore years and ten to catch his fox. He’s a master of colliding opposites. Many people don’t get it’ as they’re so used to reading words not poetry. |

| Our Bog is Dood | Stevie Smith | A bit like The Solitary Huntsman we find it difficult to go beyond a picture of an adult trying to get sense out of children. One of the clevernesses is that I know children who are just like that; with their fantasy worlds, irrational determinations and willingness to take their own side even if it’s meaningless words. What a weird ending… How about (if you can) un-picturing children and un-picturing a stuffed-toy or imaginary-creature. Now replace Bog is dood with God is dead (we mean living)(we think). Oh! She’s taking a big stick to the Church. Now it’s a completely different poem. The observations are still sharp but of different things. “How do you know your god is dead(living)(etc)?” brings a wild retort, just like asking someone to prove their God exists. Then the undeniability of their vision ends with a hardly childish You shall be crucified. They admit they don’t know what their God is but we are wholly his. And they can’t agree amongst themselves in the next verse. Now there’s more hope for the ending. Good riddance to the bloody lot of them! Being switched-on to how poetry works turns this from an oddity into a brilliant bit of mischief. |

| The Shadow People | Francis Ledwidge | An example of the genre of pastoral poetry where there is a little bit an outsider will never understand. |

| Many red devils | Stephen Crane |

Surrealism. Even more remarkable since it must have been written in the 19th century. I like the struggle to get at whatever this red stuff is, and either wipe it away or take it. (It’s never going to be fully explained.) |

| In the desert | Stephen Crane | I can see this as a painting by Hieronymus Bosch. Nasty, creepy, surreal and I don’t want to go there. There are thousands of gibberish poems around. In my view this is on the right side of incomprehensible because it shocks and scares. |

| The Guitar | Federico García Lorca | How do you write a poem about evocative lament when the music itself does the job already? By taking romantic images and strange personal diversions where dreaming takes us. |

| Conclusion | ||

| There are sort-of rules for poetry. Rhyme isn’t one of them. Drawing in the reader is a good sign. Liminality is about a ghost-glue that connects layers.

Explore the lives of the poets, and of course see if you can find more cracking good stuff… …And don’t be afraid to say you don’t think much of one-level doggerel or the pretentious bolloks I call posey |

||